Why the Sinful Woman?

a brief introduction to my forthcoming book, She Who Loved Much: The Sinful Woman in Saint Ephrem the Syrian and the Orthodox Tradition

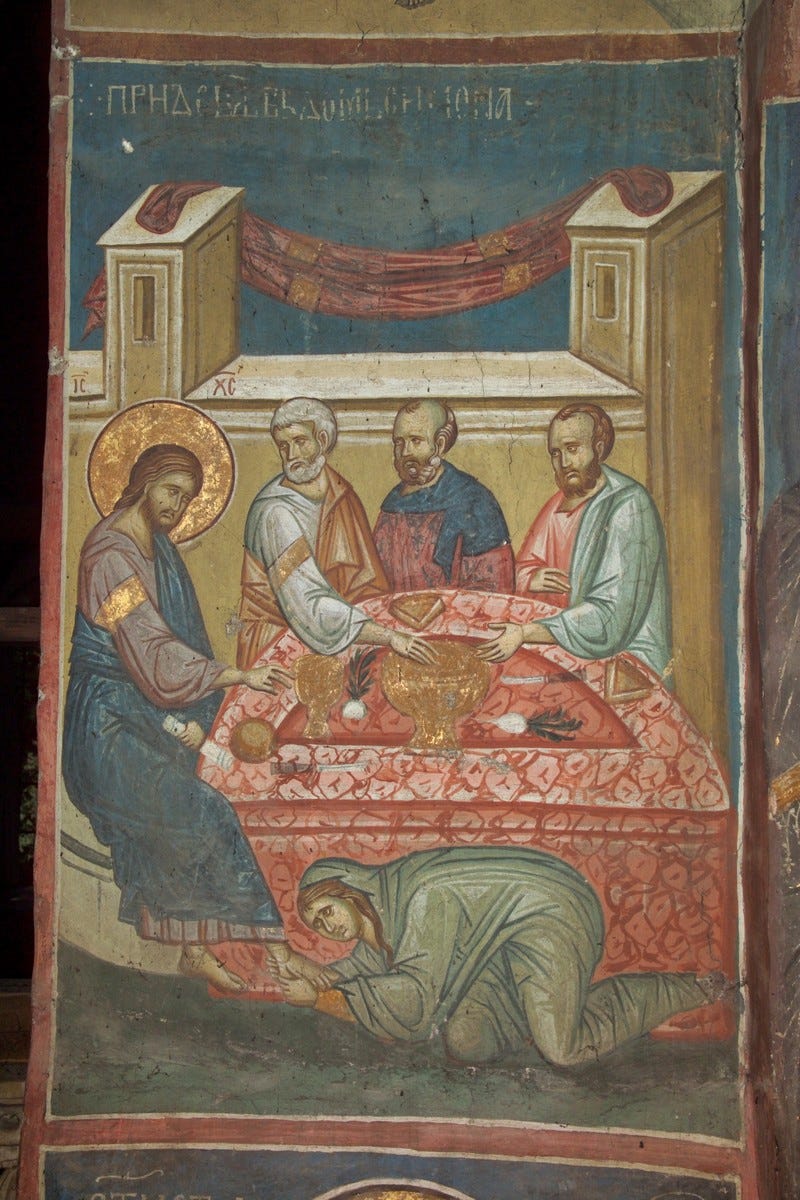

The best stories surprise us. A story is told in the New Testament, in different forms in each of the four Gospels, about a woman who anoints Jesus with precious oil. A surprising event indeed, as witnessed by the reaction of those who behold her actions. Even with the differences in the four Gospel accounts, each Gospel tells of someone reacting not too kindly to the woman’s surprising actions. Luke’s version of the story (7:36–50) stands apart, for only here are we told something about the woman. She is called a sinner, though with no other details about who she was. Luke’s story of the sinful woman who anoints Jesus is full of narrative surprises. She bursts onto the scene unannounced, and what begins as a story of Jesus dining with Simon becomes a story about this woman. The story is also unexpected in its attention to the senses. In Luke’s version, the sinful woman goes so far as to wash the feet of Jesus with her tears, wipes his feet with her hair, and kisses his feet.

Another surprise comes with the conclusion of the story in Luke’s Gospel. Jesus turns the attention to Simon. Not only does Jesus question why Simon failed to do any of the things the sinful woman did, but he also questions Simon’s very thoughts. Surprisingly, we are given access to a character’s interior thoughts, something that is rare in biblical narrative. When Jesus questions Simon, he uses a parable about debtors who are forgiven their debts. Jesus interprets the meaning of the parable, and proclaims that the woman’s sins are forgiven, “for she loved much.”

Then He turned to the woman and said to Simon, “Do you see this woman? I entered your house; you gave Me no water for My feet, but she has washed My feet with her tears and wiped them with the hair of her head. 45 You gave Me no kiss, but this woman has not ceased to kiss My feet since the time I came in. 46 You did not anoint My head with oil, but this woman has anointed My feet with fragrant oil. 47 Therefore I say to you, her sins, which are many, are forgiven, for she loved much. Luke 7: 44-47 NKJV

The sinful woman’s story does not end here. Stories arose to fill in the gaps of the narrative. Writers of homilies and hymns began to develop a back-story for the sinful woman. In these poetic creations, they created fictive speeches and interior monologues, all in attempts to understand more fully who she was and to explain its importance. Starting in the late fourth century, Syriac and Greek writers begin to imagine parts of the story that go beyond the biblical narrative. They wonder—Who was this woman? Where did she come from? How did she acquire the precious oil? How did she enter the house of Simon uninvited? What did she think to herself as she undertook these bold actions? In the process of pondering these questions, extra-biblical characters were introduced, such as the myrrh-seller, and narrative details were fleshed out about what happened before the events recorded in the Gospels. Over time, the sinful woman became a paradigm of repentance, whose actions and interior disposition model for the faithful what it means to repent and boldly approach Christ.

In the homilies and hymns about the sinful woman, it is understood that we are encountering something outside of the Gospel account. This allows authors to imagine events not in the Gospel of Luke and to explore what the sinful woman might have experienced and what she might have said, both to others and to herself in her inner thoughts. Fiction often carries negative connotations, but I use it in a way similar to how J. R. R. Tolkien describes the workings of the fairy-story—these accounts are “subcreations”:

What really happens is that the story maker proves a successful “sub-creator.” He makes a Secondary World which your mind can enter. Inside it, what he relates is “true”: it accords with the laws of that world. You therefore believe it, while you are, as it were, inside. The moment disbelief arises, the spell is broken; the magic, or rather art, has failed. 1

Stories about the sinful woman’s back-story, and the representation of her inner speech and her innermost feelings and desires, create a fictional story-world. The fullest version of her story comes from a homily attributed to St. Ephrem the Syrian, though it survives in Greek. But more on that later.

She Who Loved Much: The Sinful Woman in Saint Ephrem the Syrian and the Orthodox Tradition

J. R. R. Tolkien, “On Fairy-Stories,” in Tree and Leaf (Cambridge: Houghton Mifflin, 1965), 37.